Modern consumer wearables (Apple Watch, Garmin, WHOOP, Fitbit, Samsung) increasingly offer stress monitoring. For the most part, they calculate stress scores using heart rate variability (HRV) or proprietary algorithms.

The promise is enticing: a single number telling you how stressed you are. But the science hasn’t fully caught up. A study in the Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science found no correlation between stress scores from the 2018 Garmin Vivosmart 4 and self-reported stress in over 800 young adults. Similarly, a 2023 Frontiers in Public Health study on the Apple Watch Series 6 showed little to no correlation between ECG-derived HRV and self-reported stress in 36 healthy adults.

That said, some more recent work has found limited but promising evidence that wearable-derived stress scores can align with subjective stress under certain conditions. These early signals suggest we shouldn’t dismiss the technology outright but instead refine it—by considering stress source, context, and multiple sensor inputs.

The Cardiologist’s View: Unpacking the Roots of Stress

It’s no surprise to me that these studies showed little correlation between self-reported stress and wearable-measured stress.

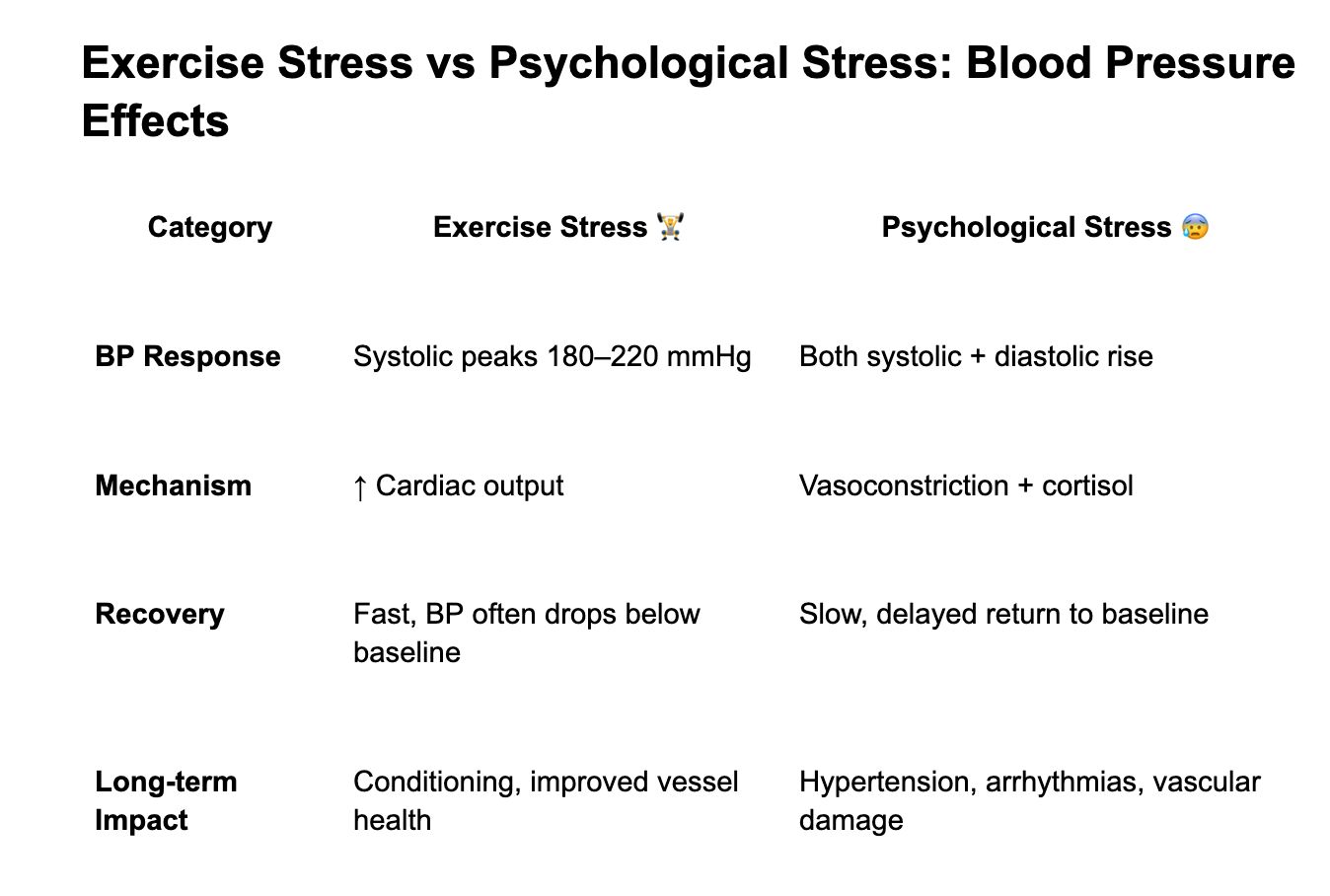

As a cardiologist, stress testing is a familiar concept, and patients often ask me about its value. In the clinic, exercise-induced stress provides useful information about heart health. But outside the clinic, when I review stress scores from wearables, exercise stress is actually the type I worry about the least—because other forms of stress may leave a much bigger cardiovascular footprint. In short, your blood pressure can spike higher during a hard run than during a panic attack, but exercise stress is physiological training, while psychological stress is vascular strain.

When we talk about “stress,” we need to be precise about its source. Not all stress is created equal.

Mental, physical, and environmental stressors each provoke unique cardiovascular patterns. Lumping them into a single number oversimplifies reality and risks misrepresenting what the body is actually experiencing.

The challenge—and the opportunity—is that a meaningful stress score must untangle these threads rather than blur them together. Below is an example of how blood pressure responds differently to exercise stress versus psychological stress.

The Case for a Better Stress Score

The biggest flaw in today’s stress scores is the word itself: stress.

Used too broadly, it flattens very different experiences from different kinds of stress into a single number.

To get it right, we need to separate where the stress is coming from—mental, physical, or environmental. The data is already there. If your device detects heat, that’s environmental stress. If it sees intense movement, that’s exercise stress. And if your phone notices changes in how you type, what words you use, or which emojis you tap 🥵😰😤, that may be psychological stress.

A better score must also go beyond HRV.

Stress shows up in sleep quality, daily activity, skin temperature, and respiratory rate. Add in posture and fidgeting patterns, and the picture becomes far richer.

Looking ahead, future wearables may also borrow signals from speech and ocular data. Stress leaves fingerprints in the voice—tone, pitch, cadence—and in the eyes through blink rate, pupil dilation, and fixation patterns.

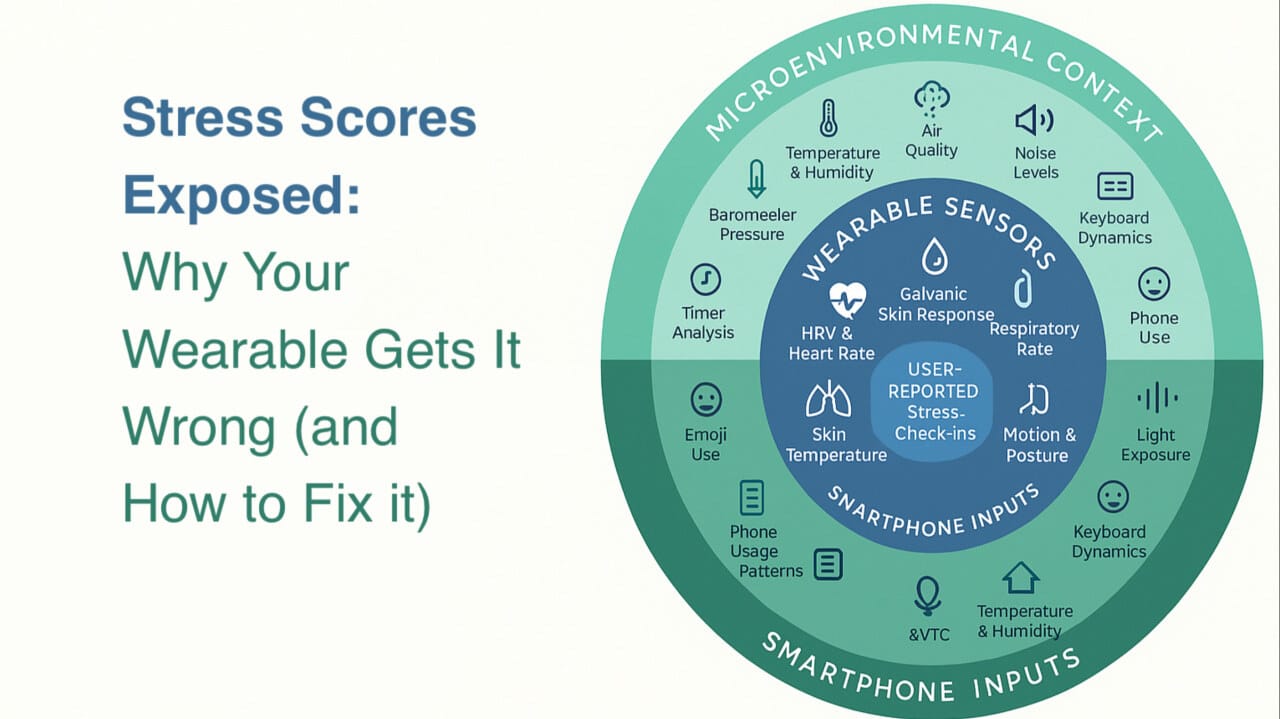

A next-gen stress score should combine physiology (HRV, respiration, skin conductance) + environment (noise, heat, air) + behavior (typing, emojis, speech). By blending signals from wearables + smartphones, we can shift from a single number to a context-aware, personalized model of stress.

While a single wearable with all these sensors may be far off, platforms like GatherMed are already bridging the gap by aggregating data from multiple devices into one unified clinician dashboard. The call for health tech is clear: move beyond incremental sensors and work toward systems that transform raw data into insights clinicians can act on.

At the end of the day, no algorithm gets it perfect—so what would you build differently? Do you have a go-to wearable you actually trust for stress tracking? If you could design your own stress score, what would you include? And do you think these scores belong in the wellness space, or should they play a bigger role in healthcare?

The Ideal Sensor Makeup for Stress Scoring

1. Core Physiologic Sensors (on wrist/ring/body)

HRV & Heart Rate (PPG/ECG): Current backbone of most stress scores.

Respiratory Rate & Breathing Patterns: Captures stress-induced shallow breathing.

Skin Temperature & Peripheral Perfusion: Detects subtle changes in thermoregulation during stress.

Galvanic Skin Response (Electrodermal Activity): Tracks sympathetic nervous system activation.

Motion / Posture (Accelerometer & Gyroscope): Identifies restlessness, fidgeting, or sedentary stress.

PPG Waveform Morphology: Goes beyond HR/HRV to infer vascular tone and sympathetic activation.

2. Microenvironmental Sensors (contextual stress)

Ambient Temperature & Humidity: Detects heat/cold stress.

Barometric Pressure / Altitude: Helps separate exertion stress (e.g., hiking at altitude).

Noise Levels (dB): Environmental stressor—persistent loud noise raises BP & HR.

Air Quality (VOC, PM2.5, CO₂): Poor air increases physiologic strain.

Light Exposure (Lux, Spectrum): Circadian alignment or disruption (stress of light at night).

3. Smartphone-Derived Inputs (since wearables are almost always tethered to a phone)

Keyboard Dynamics: Typing speed, errors, pauses → indicators of cognitive load.

Word Choice / Sentiment in Texts: Subtle language shifts may mirror mood or stress.

Emoji Use Patterns 😀😰: Reflects affective state in informal communication.

Voice Analysis (during calls or voice notes): Pitch, cadence, tone—stress “fingerprints” in speech.

Phone Usage Patterns: App switching, scrolling, late-night use → behavioral markers of stress.

4. User-Reported Layer

Micro-Surveys / Check-ins: Anchor physiologic data to lived experience.

Contextual Prompts: “Were you exercising, working, or resting when stress was detected?”

For Readers interested in How Popular Wearables Calculate Stress

WHOOP – Stress Monitor

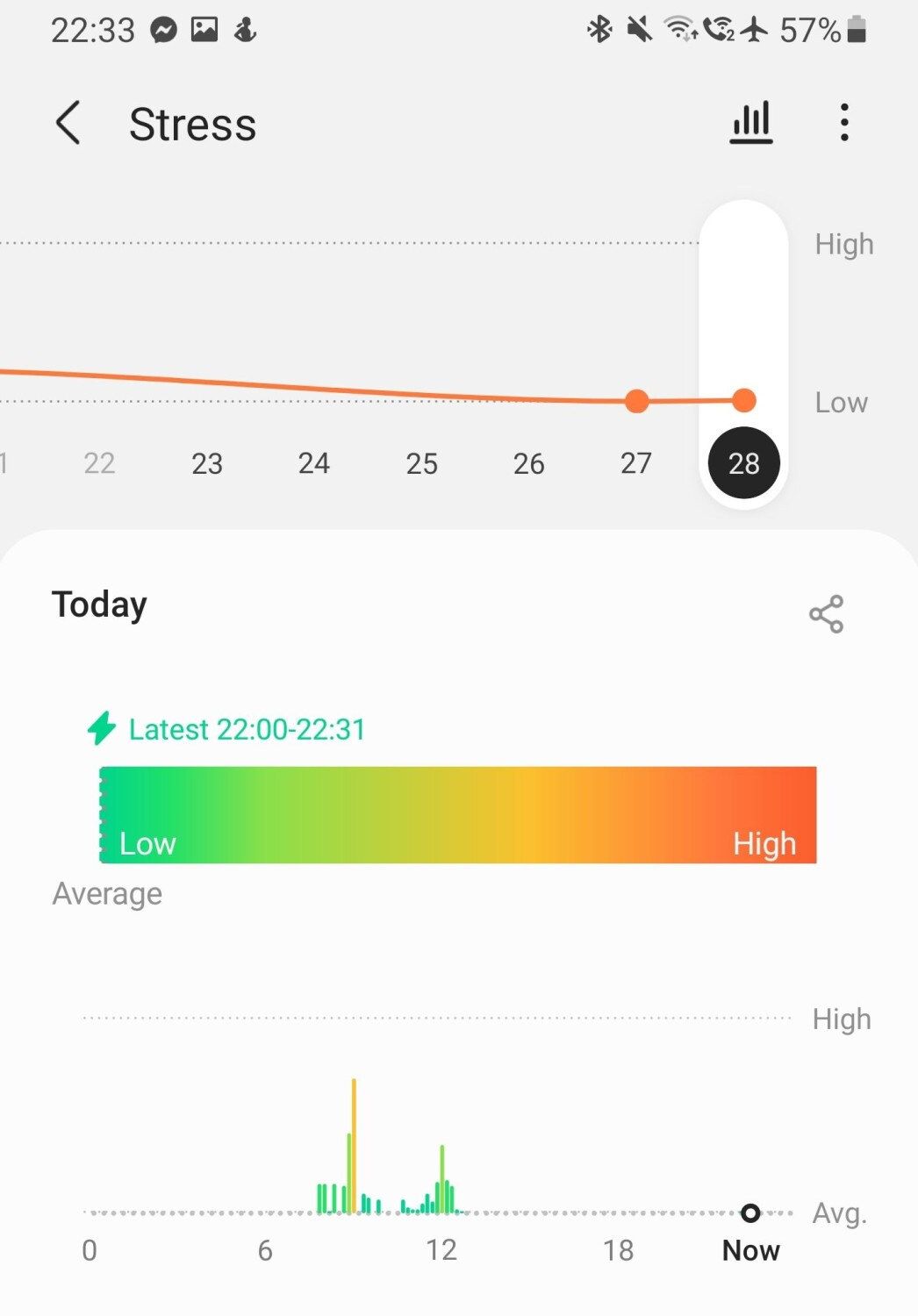

Samsung Healthcare Galaxy Watch – Stress Level

What it is: Stress estimate based on HR + HRV, via Samsung Health.

How you measure: Tap “Measure” or enable continuous mode.

What you see: Stress gauge + breathing exercises, with synced trend tracking.

Key limit: The algorithm is simplistic—heart rate spikes can be misread as stress, even if you’re just excited.

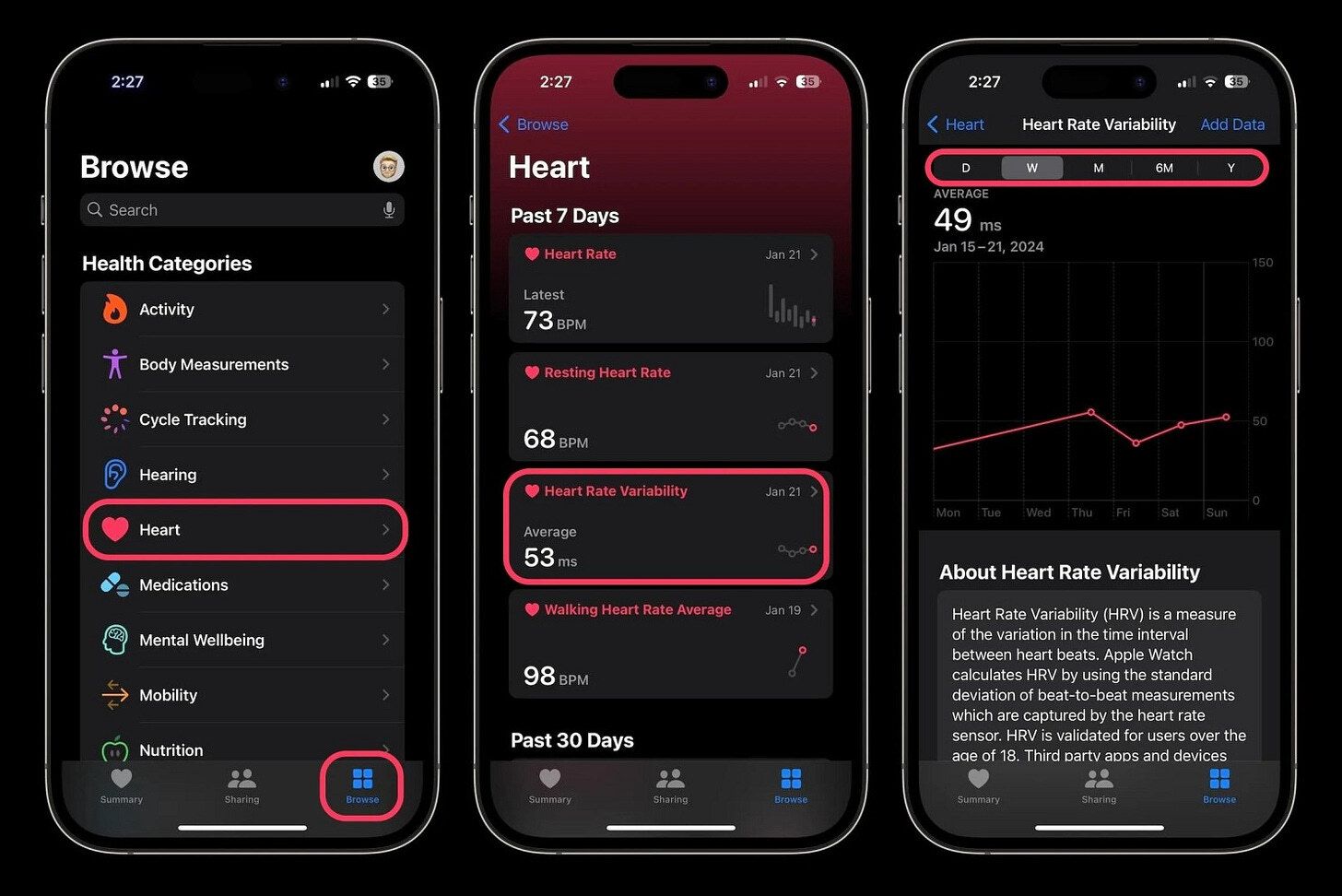

Apple Watch – HRV (No Native Stress Score)

What it tracks: HRV using optical HR during rest and workouts.

How to use: Data visible in Health app; no stress number, third-party apps required.

What it shows: HRV trends; higher HRV = recovery, lower HRV = stress/fatigue.

Caveat: HRV logged only during calm states; stress episodes with high HR may not be captured.

GarminWearables – Body Battery™

What it is: 0–100 “energy gauge,” like a fuel meter.

How it works: Combines HRV, stress, sleep, and activity.

What you see: A charge/depletion graph, syncable in Garmin Connect.

Note: Proprietary algorithm. Exercise and excitement can look like stress.

References:

As a physician who hopes to use medical-grade wearables in the future, I appreciate the hard work below in advancing the science.

Garmin

Device: Garmin Vivosmart 4.

Study Design: 29-participant pilot + 60-participant main study (total ~89, mix of male/female). Participants wore a Vivosmart 4 and a Polar H10 ECG chest strap simultaneously during controlled tasks: resting baseline vs a mental arithmetic stress task in the lab. Findings: Garmin’s proprietary “Stress Level” score (based largely on HRV) rose significantly during stress tasks and differentiated stress vs rest conditions. The Garmin stress score showed significant correlations with physiological measures: it correlated with elevated heart rate and with decreased HRV metrics like RMSSD (a time-domain HRV index). This suggests the Garmin stress metric does capture autonomic changes induced by mental stress. However, results also indicated sex and baseline HRV moderated responses (e.g. those with lower resting HRV showed larger stress responses).

Publication: Preprint (Tel Aviv University study), Jan 2025. (Not yet peer-reviewed, but adds evidence of validity in a controlled setting.)

Device: Garmin Vivosmart 3 wristband (uses Firstbeat HRV-based stress algorithm).

Study Design: 657 information workers wore the device 24/7 for 8 weeks, providing 14,695 momentary self-reports of stress, mood, anxiety, etc. A follow-up with 327 participants repeated stress surveys after ~1 year. HRV features were computed from the wearable’s inter-beat intervals over various time windows. Findings: Extremely small associations were found between wearable-derived HRV and perceived stress in real life. HRV metrics explained only ~1–2% of the variance in daily stress levels. For instance, HRV during work hours had a slight predictive value (R^2 ~0.03) but overall marginal ability to predict self-reported stress. Authors note that well-known lab findings (HRV decreases with stress) do not translate strongly to natural settings, due to confounders and individual differences.

Published: JMIR Hum. Factors, Sep 2022.

Apple Watch

Device: Apple Watch Series 6 with ECG app. Study Design: 36 healthy participants wore an Apple Watch for 2 weeks of real-life monitoring. They took 30-sec ECG recordings ~6 times/day and reported stress levels via DASS-21 and a Likert-scale questionnaire (Ecological Momentary Assessments). Findings: Little to no correlation was found between short-term HRV from the watch and self-reported stress. Repeated-measures ANOVA showed no significant differences in HRV between high vs low stress reports, and correlations between various HRV features and stress scores were very weak (though occasionally significant due to large sample size). Authors conclude that a 30-sec Apple Watch ECG HRV reading cannot reliably quantify acute perceived stress with traditional analysis (essentially “basically zero” correlation in everyday conditions), although they note that adding more sensors or machine-learning might improve detection.

Published: Frontiers in Digital Health, 2023.

Device: Apple Watch (series not specified, PPG-based HR sensor).

Study Design: 20 healthy adults underwent a 5-min relax session (calming video) followed by a 5-min mental stress task (Stroop test) while wearing an Apple Watch and a Polar H7 ECG chest strap. Findings: The RR intervals from Apple Watch showed high agreement with the ECG (reliability >0.9), albeit with occasional missing data segments. Apple Watch–derived HRV indices (e.g. RMSSD, HF power) significantly reflected stress responses – during the cognitive stress task, parasympathetic-related HRV metrics dropped (HF power and RMSSD decreased in stress vs relax).

Publication: Sensors, Aug 2018.

Fitbit (now part of Google)

Device: Fitbit Versa 2.

Study Design: 34 adults underwent the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST: including an impromptu speech and mental arithmetic under pressure) while wearing a Fitbit on the wrist and a Biopac ECG on the chest. Heart rate responses were analyzed across the TSST phases (anticipation, stressor, recovery). Findings: The Fitbit’s heart rate data did reflect the stress response – HR increased significantly during the speech and math stress phases and dropped in recovery, paralleling the ECG readings. In terms of capturing relative changes (timing and magnitude of HR increase due to stress), the wearable showed “acceptable accuracy”. However, when assessing absolute agreement, there were poor agreement indices between the Fitbit and ECG (especially at high stress-induced heart rates). In other words, the Fitbit could indicate that “HR is rising with stress” (useful for detecting a stress occurrence), but its exact HR values didn’t always match the ECG. Conclusion: the Fitbit can be used in research to monitor stress-induced HR trends, but it “cannot replace an ECG” when precision is critical.

Published: JMIR

Device: Fitbit Charge 5 (with optical HR and EDA sensors).

Study Design: 55 undergraduate students (≈19.4 years old) wore a Fitbit on one wrist and an Equivital EQ02 research-grade monitor (ECG + skin conductance) on the body while completing a social stress test (public speaking or similar) and a control task. This allowed one-to-one comparison of heart rate and electrodermal activity (EDA) measures from the consumer device vs a gold-standard. Findings: For heart rate, Fitbit showed moderate correlation with the reference (r ~0.45–0.58). For EDA (skin conductance level changes), correlation was lower (r ~0.42–0.50). Intraclass correlation coefficients were also modest (HR ICC ~0.53–0.72; EDA ICC ~0.46–0.64). Bland-Altman analysis revealed systematic errors: the Charge 5 underestimated peak heart rates by 24–32 BPM and tended to overestimate absolute EDA levels by ~±10 microSiemens relative to the reference. Conclusion: The Fitbit captured general trends (when stress raised or lowered HR/EDA), but showed notable accuracy limitations and bias. The authors advise caution in interpreting raw stress metrics from such consumer devices, as short-term values may deviate from clinical instruments.

Published: Psychophysiology (Society for Psychophysiological Research), Aug 2025.

WHOOP

Device: WHOOP 3.0 wristband (PPG sensor for HR and HRV).

Study Design: Large-scale retrospective analysis by WHOOP Inc. data scientists. 23,665 exercise events (“runs”) and 8,928 self-identified high-stress work periods were extracted from free-living data of users, with each user’s HR and HRV tracked continuously around those events. Only periods of no motion (“HR_motionless”) were analyzed to get clean HR/HRV signals. Findings: Clear physiological signatures of stress were observed. For example, after moderate/vigorous exercise, heart rate remained significantly elevated for up to 3 hours post-run and HRV (RMSSD) was significantly suppressed for 5 hours post-exercise. During and after reported high-stress work events, HR was acutely elevated and HRV dropped compared to baseline periods. In fact, HRV tended to be lower during the stress events and remained significantly depressed for 1.5–5 hours afterward. These results demonstrate that wearables can capture prolonged stress responses in the wild (sustained autonomic arousal long after a stressor).

Publication: PLOS ONE, June 2023

Device: WHOOP (various generations).

Study Design: An observational longitudinal study of 170,000+ WHOOP users over 13 months, analyzing over 7.9 million person-days of data. Users self-reported monthly mental health status via surveys (Perceived Stress Scale for stress, GAD-2 for anxiety, PHQ-2 for depression), which were matched with their wearable metrics (resting heart rate, HRV, sleep patterns, etc.). Findings: There were strong links between the wearable’s physiological metrics and mental well-being. Higher HRV and lower resting HR correlated with significantly lower perceived stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms across the cohort. Users with more consistent sleep schedules (regular bed and wake times) also reported better stress and mood outcomes, independent of total sleep duration. Notably, spikes in self-reported stress often preceded measurable physiological changes: in months where a user reported higher stress, their next weeks showed elevated resting heart rate, reduced HRV, and more irregular sleep timing. This indicates that subjective stress is mirrored by a lagging “physiological trace” – wearables catch the body’s response to sustained stress (e.g. lower vagal tone/HRV) even if the stress is self-perceived.

Publication: J. Med. Internet Res. (JMIR), June 2025.

Multi-Device Validation

Devices: Six popular wearables – Apple Watch Series 6, Garmin Forerunner 245, Polar Vantage V, WHOOP 3.0, Oura Ring Gen2, and Somfit patch.

Study Design: 53 healthy adults spent a night in a sleep lab, wearing all six devices simultaneously, plus reference devices: polysomnography (for sleep stages) and ECG (for heart rate/HRV). While primarily validating sleep tracking, the study also evaluated resting HR and HRV accuracy during overnight periods. Findings: All devices could reasonably detect sleep vs wake (≈88% agreement with PSG for total sleep time), but most struggled with detailed sleep staging (as expected). For heart rate, Apple, Garmin, Polar, Oura, and WHOOP all showed small errors overnight, but WHOOP was the most precise (HR error ~1 bpm). For HRV, there were larger differences: WHOOP had the smallest error in RMSSD (std. dev ~3.9 ms vs ECG), whereas others had substantially higher error (std. dev ~28–47 ms). In fact, the WHOOP was ~99% accurate for nocturnal HRV compared to gold-standard, outperforming the Apple Watch, Garmin, etc., whose HRV accuracy ranged roughly 25–70% in this trial. Device-specific note: High nocturnal HRV accuracy suggests a device can establish a good baseline for recovery/stress; however, this was in controlled, motion-free conditions (sleep). Active-daytime readings for those same devices likely have more noise (motion artifacts), which aligns with other studies above.

Published: Sensors (AIS-CQUniversity study), Aug 2022.